The Shape of Work

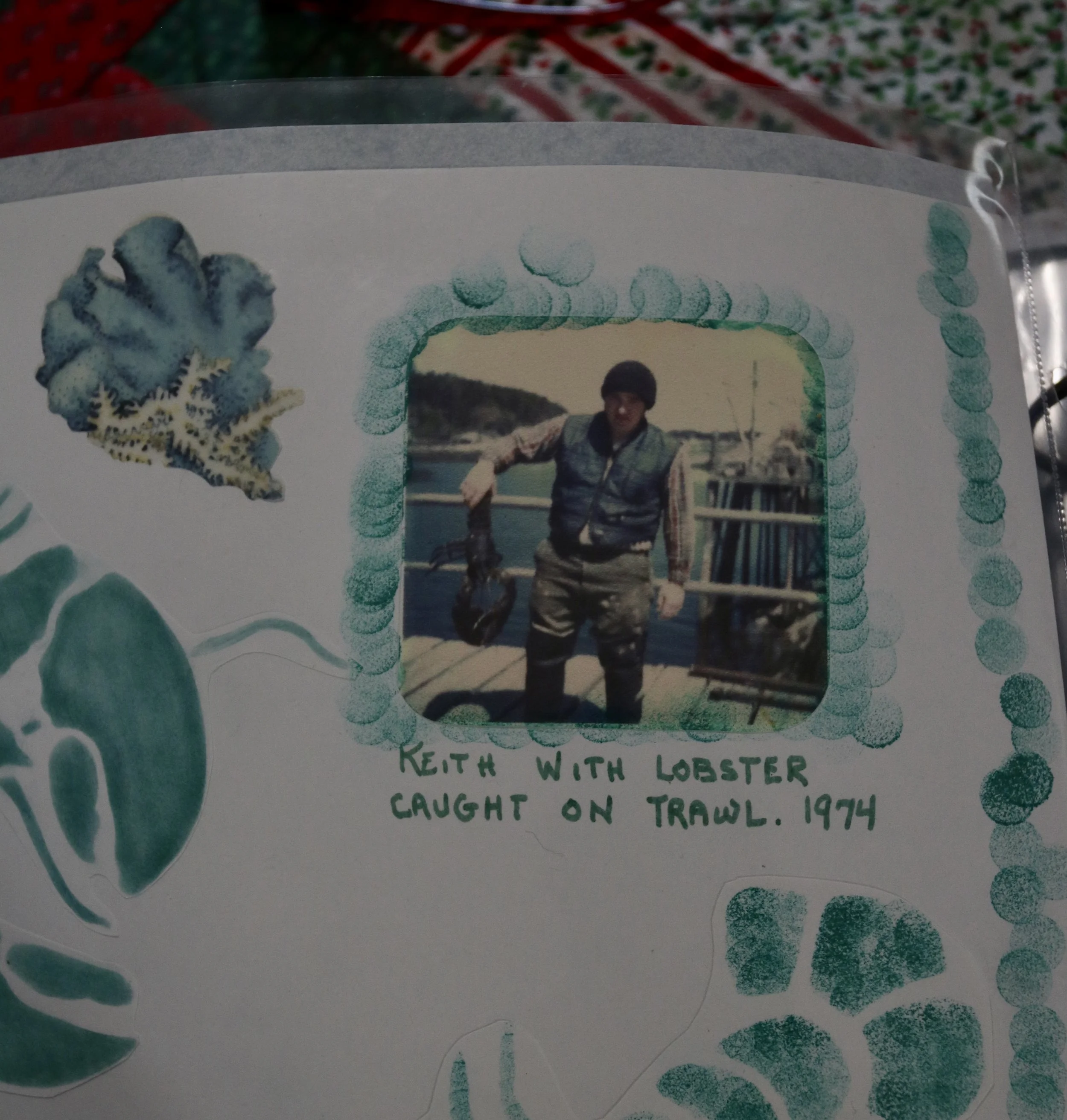

ON A DRIZZLING morning with the wind blowing steadily, Robin Wallace’s husband Keith drove out of Sebasco to go hauling. He wasn’t expected back until late afternoon. It was October of 1974 and Robin was a new mother. The Wallaces were in their early twenties, just starting their life together. Their first born daughter, Darcy, was 10-months-old.

That autumn was wet and cold–wetter and colder than the one we’ve just passed through, these 51 years later. Robin settled in for a quieter, drier time at home with little Darcy. A short while later, however, Keith’s truck pulled into the drive. His sternman was sick, and to haul a decent amount of traps, he needed another set of hands, so how about Robin comes out to help for the day?

The way Robin tells it, with her characteristic humor and her soft, yet commanding voice, I can picture little pieces of how that very first day might have gone. They had an infant daughter, in case Keith had forgotten, Robin reminded him. Sure. Keith knew. Leave little Darcy with Robin’s mother next door–infant problem solved. Okay, but what would Robin use for gear? She had no boots and it was cold, wet and blowing out there. And what about hauling gear?. Keith had boots, gear, gloves and a rebuttal for everything. And couldn’t she hurry up? The day was passing and already they’d be hauling fewer traps, which meant less money. This world doesn’t slow down for anyone–and especially not for those who work around the tides. So although Robin’s mother protested (“But you’re a girl! Girls don’t do that!”), Darcy was left at Nana Coffin’s house and Robin went to sea.

“It was cold. It was raining. I was complaining,” Robin laughs now. She wore size 11 boots, stuffed with newspaper and big socks. Keith tied up her oversized woolen pants with a string for a belt. She climbed from the wharf to the War Daddy like a big-footed clown. She says that first day, all she did was put bait on the pins and lay them on the bucket. Her gloves were too big and anything that took an ounce of dexterity, which is, in my experience, just about everything in lobstering, was a pain. And, of course, lobstering as a woman can come with the usual exasperating hurdles. One day, a few months later, Keith treated Robin to a sandwich. While he was inside ordering and she was waiting outside, two fishermen walked by, took one look at Robin in her oversized gear, and said, “Now, what’s that?” So, Robin tells me, the next time she went hauling, “I painted my fingernails, wore earrings and blush.” That was the beginning.

That first day rolled into the first month. Then a year passed and a decade and then two. This is how time goes, in ripples and waves that make the broader currents of tides until you look up from the work and see that life’s seasons ebb and flow, day in and day out, in long patterns and short, made up of all kinds of stories.

I LIKE NARRATIVES like these. I like listening to, studying and telling them. It’s the unexpected curve that brings a story to life. That curve is itself a type of question. It asks the listener to sit up, look around, take stock of what’s shifted. What would have happened if just one detail in the plot line were swapped for something more ordinary? And no surprise–I like listening to stories about the water best. It’s no surprise then, considering all this, that I like listening to Robin tell all the twistingly unexpected stories of how it was her life got led to the water

I know that I’m likely not doing Robin’s story justice, relaying it here. You’ve got to get it straight from Robin to feel the full gritty hilarity of that first season and, if you listen carefully, to hear how it is, against the material odds, a person falls in love with working on the water. Maybe I’m putting too many of my own words in her mouth, trying to turn it into a Hallmark script. Robin would tell it with the right nuance to make a lasting story.

Robin and Keith’s second daughter, Morgan, was born in 1982. Eventually, as Darcy and Morgan grew, the Wallace family of four went out hauling together. A lobsterman who has fished the same water his or her whole life knows the bottom, where mud ends and gravel begins, where shoals hide at high tide, what little canyons will tip traps. Sometimes, when I’m out on a vessel with someone who has fished as long as they’ve made memories, no matter if it’s here in the Gulf of Maine, out in the North Pacific or in the near-shore waters of the Labrador Sea, I know that when I look at the water, the rocks, the land and currents, I’m seeing so much less than them. It’s as though I’m looking at a sheet of music I cannot read or listening to a language I don’t understand. I can see and hear that there is something to be known there. But I know that I will never quite know it, not how someone who has worked the water their whole life does.

Robin says that one day when the four Wallaces were out hauling strings, Darcy started wondering how much work was left to go. Morgan said, without a hitch, “Ten strings.” The way Robin tells it, it's many small moments like these that made clear to her how in love with the water her youngest daughter was. As it so often goes, passion follows curiosity around in a circle, the one deepening the other. At the end of her undergraduate degree, Morgan called home. “I want my own boat,” she said. So Keith helped her out. According to Robin, he was over the moon to have a child who wanted to carry on his family’s long fishing legacy.

I’M A NEWCOMER to Phippsburg who’s worked in fisheries elsewhere. I often look back on my life, flabbergasted by its shape, the varied roles I’ve had and the education I’ve received–some in classrooms, sure, but mostly out. Here in Phippsburg, educational diversity is proving useful as I try to listen to all the stories suddenly commingling on this peninsula.

When Robin and I talk about fishing jobs, we chuckle about their indelicacies. The first time she and I ever had a good long chat, we reflected on how the terrific efficiency necessary in commercial fishing never seems to leave the body. When you’re working, you’re working, we agreed. You train not only your body to move fast, but your mind too. The best fishermen are smart about their movements. The whole day sometimes feels like juggling infinite tetris problems all at once. Robins describes how, even now, decades after she stopped sterning, when she leaves her bedroom in the morning, habit makes sure she doesn’t have to go back in. Little time-saving things like this add up in a day at sea.

We laughed at how we both still eat our meals in a frenzy–because on a boat, the days are not cut up into steady, measurable blocks of tidy time, but undulate with the rapidity of the hauler block or the length of the steam between strings. There’s no time to linger over anything, let alone meals. “There was only a tiny little place for me to sit,” she remembers about those early days on the War Daddy. As she talked, I recalled how good I got at sleeping upright or braced against swells. And though it’s been years, I still prefer sleeping in small spaces, like the teeny, curtained bunk beds in the staterooms of factory vessels. Talking to Robin, small details that I thought were lost come back to me. I think about how the shape of the work shapes the life.

HISTORY COMES IN sets, building on the substrate of the present, pushed in by the blows of the past. We’re all living inside these wave patterns, but in Phippsburg, I’d argue that it’s folks out on the water who are lately feeling the change the most and from all directions. Yes, times are changing, everyone says. Changing waters and mounting digital reporting and the shifting neighborhoods of Phippsburg’s historic fishing villages make fishing a different game. “It’s not fun anymore,” fishermen say. There are stories written into every simple sentence. And in this characteristically undramatic phrasing, I hear an existential subtext: people are losing the culture they were born into. These stories and their sudden curves leave me questions. If the shape of the work is being changed season over season, how is the shape of the life changing too?

Fishing, I’m told, can make a life’s career that never gets boring. It’s often autonomous work, shaped not by a boss or clock but one’s own indefatigable work ethic and the patterns of the water, the seasons and market. Fishing of all kinds has long been a fine way to make a living in Maine. Indeed, commercial fishing predates Maine itself, and certainly predates Maine’s branding as “Vacationland.” There is always some new puzzle to stimulate the mind.

It is work that requires an education so diverse it’s tricky to list all its pieces. A fisherman needs seafaring knowledge, a captain’s license, electrical skills, oceanographic and biological know-how, wily creative problem solving at every turn, financial accounting, carpentry, determination. Lately, fishermen also need to speak the language of legislation and be computer savvy. Among other, more localized shifts, it’s the addition of these last two skills, pushed onto the fishing community by decisions often made in inland offices, that is changing the shape of a fisherman’s day.

All over the world, folks find their way to the nearest shore, as though some manageable semblance of the patterns of life can be found there. I know that this is, in part, why I find marine work so compelling. Because to work on the water is to live, labor and grow in tandem with these wave patterns, to rely on them and thus to know them intimately and be shaped by them day in and day out.

I’M STUBBORNLY OF the opinion that stories always start before people notice, in nonhuman things. Long ago, ice sheets compressed tall mountains, leaving these long fingers of land that extend into the Gulf of Maine. Oceanic currents and weather follow big global patterns, and push all sorts of tides onto our shores. Wavebreak shapes Phippsburg’s edge one way on the eastern side and another in the western inlets. The mudflats, deep coves, tall bluffs and low roads swamped lately at high tide are all products of time’s deep story. We’re caught here, neighbors and strangers, living on the surface of something old.

People have smaller ways of talking than mountains and tides. We all tell stories in different ways–in photographs and words, with action and silences. But the refrain lately, here and everywhere, is that people feel unheard. It makes sense. There are likely more ways to shut one’s ears than there are to listen.

When I was a graduate student studying creative writing, my friends and fellow writers came to know what to expect from me: rants about fish, money and the people who harvest from the sea. I’ve been going on about the same stuff for years now. I go on about this fishing stuff because everybody’s lives are busy, loud, tiring. I know that without someone like me yammering, it’s too easy to forget who it is who caught the lobster, who it is who dug the clam, who it is who drove the reefer truck from the wharf to the fish market’s back door.

THE OTHER DAY, while riding back to Sebasco, Robin said she knows she and Keith have done so well, been so resilient in all this change, because they worked together for so long. “And worked like hell,” I added. Robin is as humble as they come, but even she couldn’t deny that yes, the Wallaces, no matter what their aim, have worked like hell. Darcy and Morgan grew up, left home for school. Darcy charged through layers of education and now runs her own speech therapy practice. When Morgan came back from college, she got her own boat and hauled her own traps. Eventually, however, life took her ashore again. She raised a family. Robin says that no matter what Darcy or Morgan are focusing on, they always bring the same concentrated intensity that they did while hauling.

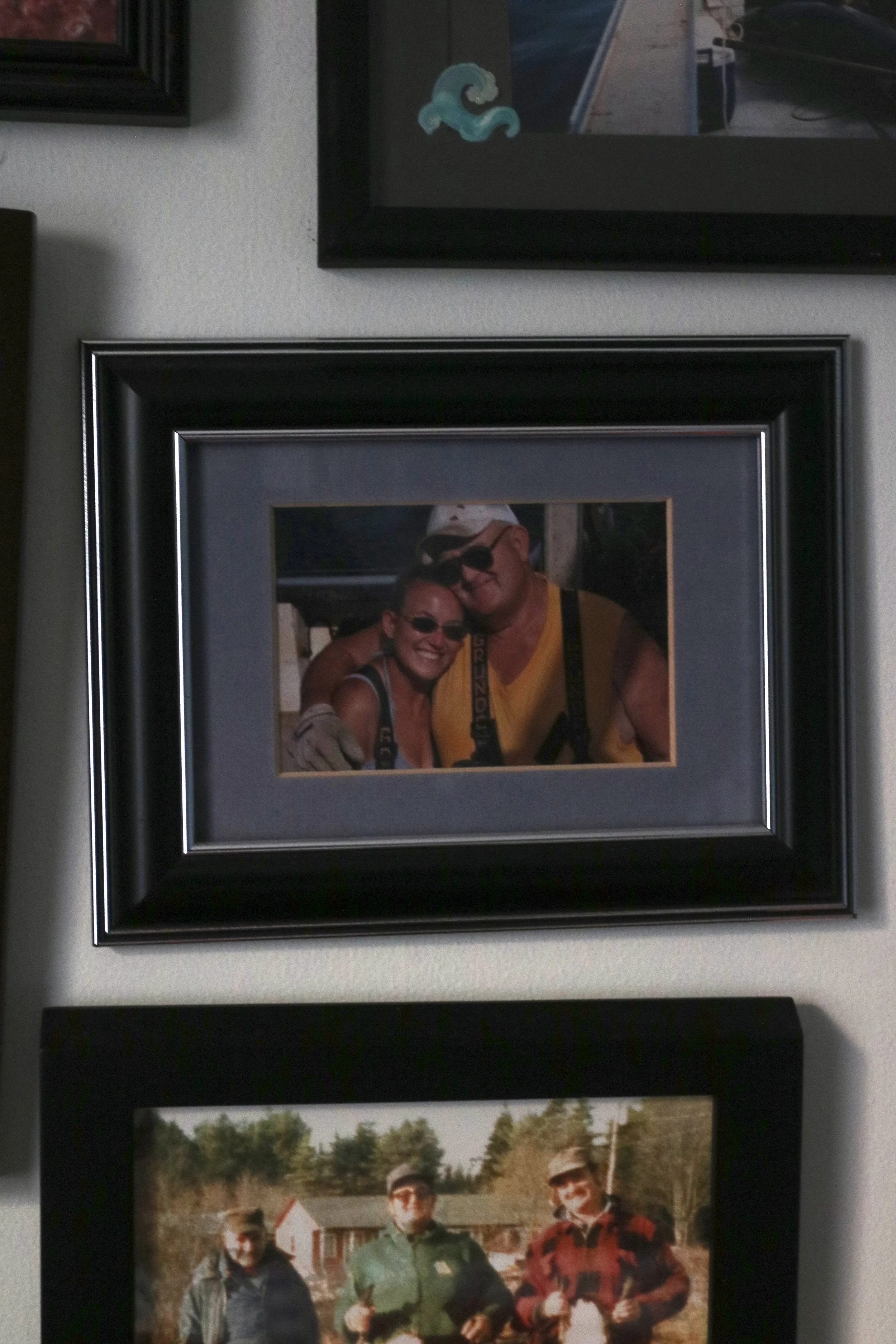

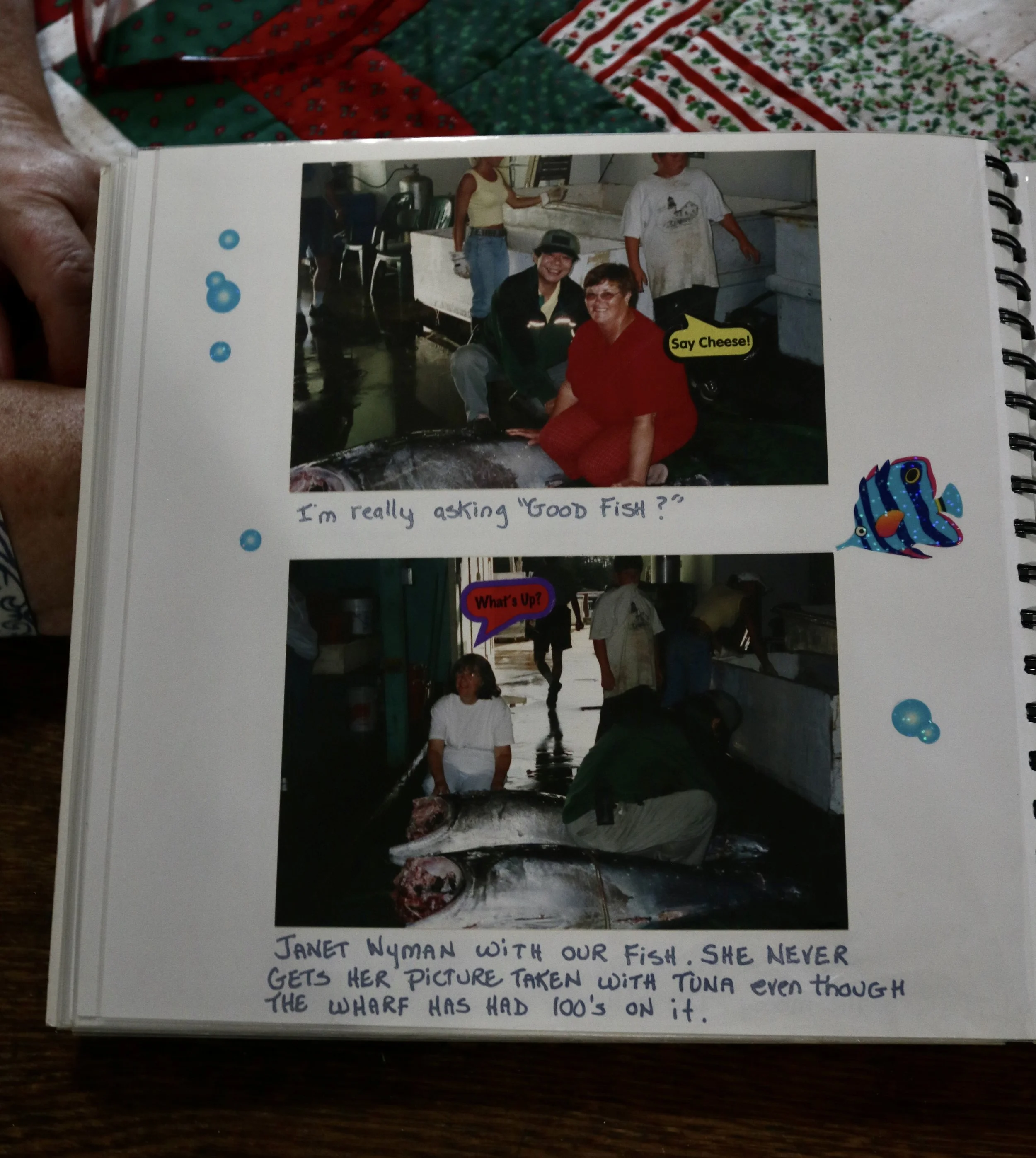

Robin is a Coffin and Keith is a Wallace. These are long-time fishing families on the New England coast. Framed photographs and paintings of fishermen, boats, brawny tuna, shorelines and family fill the Wallaces’ Sebasco walls. The coffee table is glass-topped and displays marine oddities. Most of the time, I feel like I kind of know what I’m talking about, when it comes to fisheries. But here in Phippsburg, I feel laughably uneducated. Standing in the Wallaces’ living room, I’m so aware of all that I don’t know, all that I’m hoping to learn, and all that families like the Wallaces can teach. When a community’s fisheries knowledge extends back generations, there is no way to catch up, to learn it all. That’s alright. It’s good to have too much to wonder about. In this Fellowship, I have the sense of being an undergraduate again, studying biology, when it felt like I couldn’t walk two steps without learning something new, getting sucked into some new story.

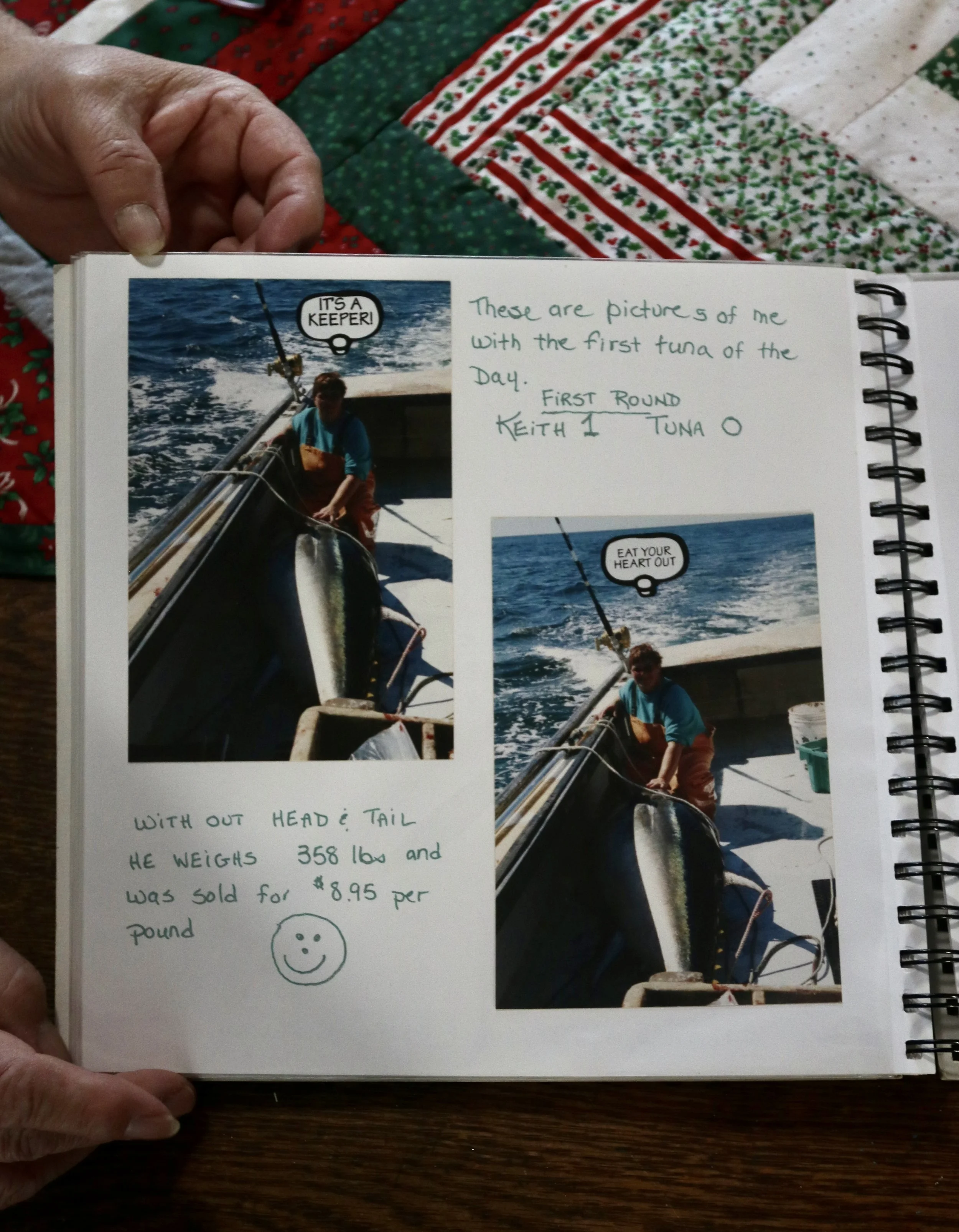

Knowing Robin and Keith just a little now, I imagine they made a powerful team. For years, they lobstered, went tuna fishing, laid mackerel nets and pulled a good life from the sea. Their combined skill, dedication to a life at sea and together makes for a spell-binding narrative. The first boat of Keith’s they worked on was named the War Daddy. But then it was called the Robin. The next boat was the Robin C. Then the Robin C 2. And finally the Robin C Too. Keith’s new boat is the Screamin’ Demon–supposedly named after their howler of a dog. But Robin says she overheard Keith tell someone that in fact both boats have been named after her. Just as they had dates at sea, they had their storms out there too. “I was put to shore,” Robin laughs. But “he’s my hero,” she told me recently, while we leafed through their family’s photo albums. I have a sense that the feeling is mutual.

Robin and Keith fished together for over two decades, until 1998 when her back said to quit. Along the way, even Robin’s mother found that she appreciated the time with the granddaughters. She welcomed the lobster her fishing daughter brought home from hauling. When I listen to Robin tell stories of fishing with Keith and of raising their daughters on the water, I hear the convergent arc of many great love stories, the kind that keep rolling on.

Robin is a grandmother now. Morgan’s daughter Sadie is a senior at Morse High School. Though I’ve never met her, I hear she carries the determination that runs thick in her family. Robin says Sadie wants to study marine science, to research the living webs of the water. Marine science is itself a way of listening. It is a listening that is becoming ever more important here on the Gulf of Maine. Into this study, Sadie will bring her family’s many generations of compounded fisheries knowledge. Her unique perspective will one be one of many crucial voices, shifting the future narrative of how we form relationships not only with the ocean but to each other.